Utopian Socialist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern

Be Utopian: Demand the Realistic

by Robert Pollin, ''The Nation'', March 9, 2009. {{DEFAULTSORT:Utopian Socialism Utopian socialism, History of social movements Idealism Radicalism (historical) Social theories Socialism Syndicalism Types of socialism

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes th ...

and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon (17 October 1760 – 19 May 1825), often referred to as Henri de Saint-Simon (), was a French political, economic and socialist theorist and businessman whose thought had a substantial influence on p ...

, Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier (;; 7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of Fourier's social and moral views, held to be radical ...

, Étienne Cabet

Étienne Cabet (; January 1, 1788 – November 9, 1856) was a French philosopher and utopian socialist who founded the Icarian movement. Cabet became the most popular socialist advocate of his day, with a special appeal to artisans who were bei ...

, and Robert Owen

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh people, Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement. He strove to improve factory working conditio ...

. Utopian socialism is often described as the presentation of visions and outlines for imaginary or futuristic ideal societies, with positive ideals being the main reason for moving society in such a direction. Later socialists and critics of utopian socialism viewed utopian socialism as not being grounded in actual material conditions of existing society. These visions of ideal societies competed with revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective, to refer to something that has a major, sudden impact on society or on some aspect of human endeavor.

...

and social democratic

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

movements.

As a term or label, ''utopian socialism'' is most often applied to, or used to define, those socialists who lived in the first quarter of the 19th century who were ascribed the label utopian by later socialists as a pejorative

A pejorative or slur is a word or grammatical form expressing a negative or a disrespectful connotation, a low opinion, or a lack of respect toward someone or something. It is also used to express criticism, hostility, or disregard. Sometimes, a ...

in order to imply naïveté and to dismiss their ideas as fanciful and unrealistic.''Newman, Michael''. (2005) ''Socialism: A Very Short Introduction'', Oxford University Press, . A similar school of thought that emerged in the early 20th century which makes the case for socialism on moral grounds is ethical socialism

Ethical socialism is a political philosophy that appeals to socialism on ethical and moral grounds as opposed to consumeristic, economic, and egoistic grounds. It emphasizes the need for a morally conscious economy based upon the principle ...

.

One key difference between utopian socialists and other socialists such as most anarchists and Marxists is that utopian socialists generally do not believe any form of class struggle

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society because of socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The form ...

or social revolution

Social revolutions are sudden changes in the structure and nature of society. These revolutions are usually recognized as having transformed society, economy, culture, philosophy, and technology along with but more than just the political sys ...

is necessary for socialism to emerge. Utopian socialists believe that people of all classes can voluntarily adopt their plan for society if it is presented convincingly. They feel their form of cooperative socialism can be established among like-minded people within the existing society and that their small communities can demonstrate the feasibility of their plan for society. Because of this tendency, utopian socialism was also related to radicalism, a left-wing liberal ideology.

Definition

The thinkers identified as utopian socialist did not use the term ''utopian

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia'', describing a fictional island socie ...

'' to refer to their ideas. Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' scientific socialism Scientific socialism is a term coined in 1840 by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in his book '' What is Property?'' to mean a society ruled by a scientific government, i.e., one whose sovereignty rests upon reason, rather than sheer will: Thus, in a given ...

which has been likened to '' scientific socialism Scientific socialism is a term coined in 1840 by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in his book '' What is Property?'' to mean a society ruled by a scientific government, i.e., one whose sovereignty rests upon reason, rather than sheer will: Thus, in a given ...

Taylorism

Scientific management is a theory of management that analyzes and synthesizes workflows. Its main objective is improving economic efficiency, especially labor productivity. It was one of the earliest attempts to apply science to the engineeri ...

.

This distinction was made clear in Engels' work '' Socialism: Utopian and Scientific'' (1892, part of an earlier publication, the ''Anti-Dühring

''Anti-Dühring'' (german: Herrn Eugen Dührings Umwälzung der Wissenschaft, "Herr Eugen Dühring's Revolution in Science") is a book by Friedrich Engels, first published in German in 1878. It had previously been serialised in the newspaper ''V ...

'' from 1878). Utopian socialists were seen as wanting to expand the principles of the French revolution in order to create a more rational society. Despite being labeled as utopian by later socialists, their aims were not always utopian and their values often included rigid support for the scientific method and the creation of a society based upon scientific understanding.

Development

The term ''utopian socialism'' was introduced byKarl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

in "For a Ruthless Criticism of Everything" in 1843 and then developed in ''The Communist Manifesto

''The Communist Manifesto'', originally the ''Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (german: Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei), is a political pamphlet written by German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Commissioned by the Commu ...

'' in 1848, although shortly before its publication Marx had already attacked the ideas of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, , ; 15 January 1809, Besançon – 19 January 1865, Paris) was a French socialist,Landauer, Carl; Landauer, Hilde Stein; Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1979) 959 "The Three Anticapitalistic Movements". ''European Socia ...

in '' The Poverty of Philosophy'' (originally written in French, 1847). The term was used by later socialist thinkers to describe early socialist or quasi-socialist intellectuals who created hypothetical visions of egalitarian

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hu ...

, communal, meritocratic

Meritocracy (''merit'', from Latin , and ''-cracy'', from Ancient Greek 'strength, power') is the notion of a political system in which economic goods and/or political power are vested in individual people based on talent, effort, and ac ...

, or other notions of perfect societies without considering how these societies could be created or sustained.

In ''The Poverty of Philosophy'', Marx criticized the economic

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with th ...

and philosophical

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

arguments of Proudhon set forth in '' The System of Economic Contradictions, or The Philosophy of Poverty''. Marx accused Proudhon of wanting to rise above the bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. Th ...

. In the history of Marx's thought and Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

, this work is pivotal in the distinction between the concepts of utopian socialism and what Marx and the Marxists claimed as scientific socialism. Although utopian socialists shared few political, social, or economic perspectives, Marx and Engels argued that they shared certain intellectual characteristics. In ''The Communist Manifesto'', Marx and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' scientific method The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientifi ...

to human social organization and were therefore not utopian. On the basis of '' scientific method The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientifi ...

Karl Popper

Sir Karl Raimund Popper (28 July 1902 – 17 September 1994) was an Austrian-British philosopher, academic and social commentator. One of the 20th century's most influential philosophers of science, Popper is known for his rejection of the ...

's definition of science as "the practice of experimentation, of hypothesis and test", Joshua Muravchik

Joshua Muravchik (born September 17, 1947 in New York City) is a neoconservative political scholar. A distinguished fellow at the DC-based World Affairs Institute. He is also an adjunct professor at the DC-based Institute of World Politics (since 1 ...

argued that "Owen and Fourier and their followers were the real 'scientific socialists.' They hit upon the idea of socialism, and they tested it by attempting to form socialist communities". By contrast, Muravchik further argued that Marx made untestable predictions about the future and that Marx's view that socialism would be created by impersonal historical forces may lead one to conclude that it is unnecessary to strive for socialism because it will happen anyway.

Social unrest between the employee and employer in a society results from the growth of productive forces such as technology and natural resources are the main causes of social and economic development. These productive forces require a mode of production, or an economic system, that’s based around private property rights and institutions that determine the wage for labor. Additionally, the capitalist rulers control the modes of production. This ideological economic structure allows the bourgeoises to undermine the worker’s sensibility of their place in society, being that the bourgeoises rule the society in their own interests. These rulers of society exploit the relationship between labor and capital, allowing for them to maximize their profit. To Marx and Engels, the profiteering through the exploitation of workers is the core issue of capitalism, explaining their beliefs for the working class’s oppression.Capitalism will reach a certain stage, one of which it cannot progress society forward, resulting in the seeding of socialism. As a socialist, Marx theorized the internal failures of capitalism. He described how the tensions between the productive forces and the modes of production would lead to the downfall of capitalism through a social revolution. Leading the revolution would be the proletariat, being that the preeminence of the bourgeoise would end. Marx’s vision of his society established that there would be no classes, freedom of mankind, and the opportunity of self-interested labor to rid any alienation. In Marx’s view, the socialist society would better the lives of the working class by introducing equality for all.

Since the mid-19th century, Engels overtook utopian socialism in terms of intellectual development and number of adherents. At one time almost half the population of the world lived under regimes that claimed to be Marxist. Currents such as Owenism

Owenism is the utopian socialist philosophy of 19th-century social reformer Robert Owen and his followers and successors, who are known as Owenites. Owenism aimed for radical reform of society and is considered a forerunner of the cooperative ...

and Fourierism

Fourierism () is the systematic set of economic, political, and social beliefs first espoused by French intellectual Charles Fourier (1772–1837). Based upon a belief in the inevitability of communal associations of people who worked and lived to ...

attracted the interest of numerous later authors but failed to compete with the now dominant Marxist and Anarchist schools on a political level. It has been noted that they exerted a significant influence on the emergence of new religious movements such as spiritualism

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century, Spiritualism (when not lowercase ...

and occult

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism a ...

ism.

In literature and in practice

Perhaps the first utopian socialist wasThomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lord ...

(1478–1535), who wrote about an imaginary socialist society in his book ''Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book '' Utopia'', describing a fictional island soc ...

'', published in 1516. The contemporary definition of the English word ''utopia'' derives from this work and many aspects of More's description of Utopia were influenced by life in monasteries

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

.

Saint-Simonianism was a French political and social movement of the first half of the 19th century, inspired by the ideas of Henri de Saint-Simon

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon (17 October 1760 – 19 May 1825), often referred to as Henri de Saint-Simon (), was a French political, economic and socialist theorist and businessman whose thought had a substantial influence on p ...

(1760–1825). His ideas influenced Auguste Comte

Isidore Marie Auguste François Xavier Comte (; 19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857) was a French philosopher and writer who formulated the doctrine of positivism. He is often regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense ...

(who was for a time Saint-Simon's secretary), Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

, John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

and many other thinkers and social theorists.

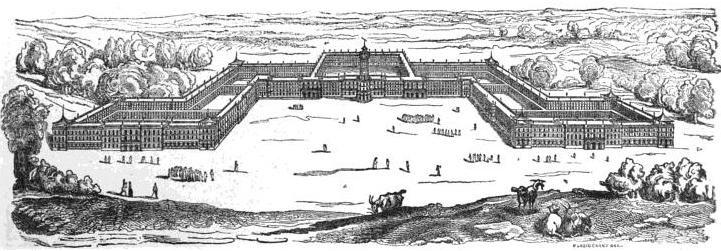

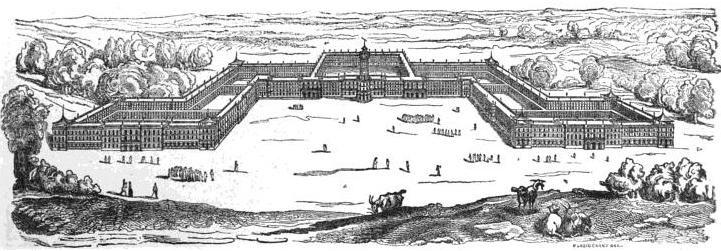

Robert Owen

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh people, Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement. He strove to improve factory working conditio ...

(1771–1858) was a successful Welsh businessman who devoted much of his profits to improving the lives of his employees. His reputation grew when he set up a textile factory in New Lanark

New Lanark is a village on the River Clyde, approximately 1.4 miles (2.2 kilometres) from Lanark, in Lanarkshire, and some southeast of Glasgow, Scotland. It was founded in 1785 and opened in 1786 by David Dale, who built cotton mills and hou ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, co-funded by his teacher, the utilitarian

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charac ...

Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 ld Style and New Style dates, O.S. 4 February 1747– 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of modern utilitarianism.

Bentham defined as the "fundam ...

and introduced shorter working hours, schools for children and renovated housing. He wrote about his ideas in his book ''A New View of Society'' which was published in 1813 and ''An Explanation of the Cause of Distress which pervades the civilized parts of the world'' in 1823. He also set up an Owenite commune called New Harmony in Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

. This collapsed when one of his business partners ran off with all the profits. Owen's main contribution to socialist thought was the view that human social behavior is not fixed or absolute and that humans have the free will to organize themselves into any kind of society they wished.

Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier (;; 7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of Fourier's social and moral views, held to be radical ...

(1772–1837) rejected the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

altogether and thus the problems that arose with it. Fourier viewed societies of factories and moneymaking as cruel and inhumane. He thought industrial development turned human existence bland and left people unstimulated. Referring back to Adam Smith's Pin factory idea, although production was roaring, one's day was filled with the same monotonous tasks. Fourier proposed a system of harmony in which people would lead fulfilling and purposeful lives by following their passions. He imagined small communities called Phalanstere which would contain workshops, libraries, and even opera houses. He envisioned people of many different passions coming together to complete tasks they had to carry out. These passions would create 810 different character types. There would be the passion of the butterfly, the fondness of engaging in many different activities. The passion of the cabalist, the desire for intrigue and plots. There would be something to account for every person's true desires. There would be no wages, but instead, people would share the profits that the phalanstery made. Fourier waited for his phalansteries to be brought to life, but this did not occur to his disappointment. Fourier wrote about people growing tails with eyes on them, six moons appearing, and the seas would turn into lemonade after setting up his phalansteries. He also wrote that humans would form friendships with wild animals and have friendly anti-tigers carry people around on their backs. His writings often led to people thinking he was a mad man. However, his ideas and writings brought to light an important question that many utopian socialists faced: how will there be work that stimulated all parts of one's personality? Fourier made various fanciful claims about the ideal world he envisioned. Despite some clearly non-socialist inclinations, he contributed significantly even if indirectly to the socialist movement. His writings about turning work into play influenced the young Karl Marx and helped him devise his theory of alienation. Several colonies based on Fourier's ideas were founded in the United States by Albert Brisbane

Albert Brisbane (August 22, 1809 – May 1, 1890) was an American utopian socialist and is remembered as the chief popularizer of the theories of Charles Fourier in the United States. Brisbane was the author of several books, notably ''Social D ...

and Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and editor of the '' New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressman from New York ...

.

Many Romantic authors, most notably William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosophy, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. God ...

and Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 17928 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame during his lifetime, but recognition of his achi ...

, wrote anti-capitalist

Anti-capitalism is a political ideology and movement encompassing a variety of attitudes and ideas that oppose capitalism. In this sense, anti-capitalists are those who wish to replace capitalism with another type of economic system, such as so ...

works and supported peasant revolutions across early 19th century Europe. Étienne Cabet

Étienne Cabet (; January 1, 1788 – November 9, 1856) was a French philosopher and utopian socialist who founded the Icarian movement. Cabet became the most popular socialist advocate of his day, with a special appeal to artisans who were bei ...

(1788–1856), influenced by Robert Owen, published a book in 1840 entitled ''Travel and adventures of Lord William Carisdall in Icaria'' in which he described an ideal communal society. His attempts to form real socialist communities based on his ideas through the Icarian movement did not survive, but one such community was the precursor of Corning, Iowa. Possibly inspired by Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

, he coined the word ''communism'' and influenced other thinkers, including Marx and Engels.

Edward Bellamy

Edward Bellamy (March 26, 1850 – May 22, 1898) was an American author, journalist, and political activist most famous for his utopian novel ''Looking Backward''. Bellamy's vision of a harmonious future world inspired the formation of numerou ...

(1850–1898) published ''Looking Backward

''Looking Backward: 2000–1887'' is a utopian science fiction novel by Edward Bellamy, a journalist and writer from Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts; it was first published in 1888.

The book was translated into several languages, and in short o ...

'' in 1888, a utopian romance novel about a future socialist society. In Bellamy's utopia, property was held in common and money replaced with a system of equal credit for all. Valid for a year and non-transferable between individuals, credit expenditure was to be tracked via "credit-cards" (which bear no resemblance to modern credit cards which are tools of debt-finance). Labour was compulsory from age 21 to 40 and organised via various departments of an Industrial Army to which most citizens belonged. Working hours were to be cut drastically due to technological advances (including organisational). People were expected to be motivated by a Religion of Solidarity and criminal behavior was treated as a form of mental illness or "atavism". The book ranked as second or third best seller of its time (after ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U ...

'' and ''Ben Hur''). In 1897, Bellamy published a sequel entitled '' Equality'' as a reply to his critics and which lacked the Industrial Army and other authoritarian aspects.

William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He w ...

(1834–1896) published ''News from Nowhere

''News from Nowhere'' (1890) is a classic work combining utopian socialism and soft science fiction written by the artist, designer and socialist pioneer William Morris. It was first published in serial form in the ''Commonweal'' journal begin ...

'' in 1890, partly as a response to Bellamy's ''Looking Backwards'', which he equated with the socialism of Fabians such as Sydney Webb. Morris' vision of the future socialist society was centred around his concept of useful work as opposed to useless toil and the redemption of human labour. Morris believed that all work should be artistic, in the sense that the worker should find it both pleasurable and an outlet for creativity. Morris' conception of labour thus bears strong resemblance to Fourier's, while Bellamy's (the reduction of labour) is more akin to that of Saint-Simon or in aspects Marx.

The Brotherhood Church in Britain and the Life and Labor Commune in Russia were based on the Christian anarchist

Christian anarchism is a Christian movement in political theology that claims anarchism is inherent in Christianity and the Gospels. It is grounded in the belief that there is only one source of authority to which Christians are ultimately ans ...

ideas of Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

(1828–1910). Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, , ; 15 January 1809, Besançon – 19 January 1865, Paris) was a French socialist,Landauer, Carl; Landauer, Hilde Stein; Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1979) 959 "The Three Anticapitalistic Movements". ''European Socia ...

(1809–1865) and Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activist ...

(1842–1921) wrote about anarchist forms of socialism in their books. Proudhon wrote '' What is Property?'' (1840) and '' The System of Economic Contradictions, or The Philosophy of Poverty'' (1847). Kropotkin wrote ''The Conquest of Bread

''The Conquest of Bread'' (french: La Conquête du Pain; rus, Хлѣбъ и воля, Khleb i volja, "Bread and Freedom"; in contemporary spelling), also known colloquially as The Bread Book, is an 1892 book by the Russian anarcho-communist P ...

'' (1892) and ''Fields, Factories and Workshops

''Fields, Factories, and Workshops'' is an 1899 book by anarchist Peter Kropotkin that discusses the decentralization of industries, possibilities of agriculture, and uses of small industries. Before this book on economics, Kropotkin had been k ...

'' (1912). Many of the anarchist collectives formed in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, especially in Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to s ...

and Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the no ...

, during the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

were based on their ideas. While linking to different topics is always useful to maximize exposure, anarchism does not derive itself from utopian socialism and most anarchists would consider the association to essentially be a marxist slur designed to reduce the credibility of anarchism amongst socialists.

Many participants in the historical kibbutz

A kibbutz ( he, קִבּוּץ / , lit. "gathering, clustering"; plural: kibbutzim / ) is an intentional community in Israel that was traditionally based on agriculture. The first kibbutz, established in 1909, was Degania. Today, farming h ...

movement in Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

were motivated by utopian socialist ideas. Augustin Souchy

Augustin Souchy Bauer (28 August 1892 – 1 January 1984) was a German anarchist, antimilitarist, labor union official and journalist. He traveled widely and wrote extensively about the Spanish Civil War and intentional communities. He was bor ...

(1892–1984) spent most of his life investigating and participating in many kinds of socialist communities. Souchy wrote about his experiences in his autobiography ''Beware! Anarchist!'' Behavioral psychologist B. F. Skinner

Burrhus Frederic Skinner (March 20, 1904 – August 18, 1990) was an American psychologist, behaviorist, author, inventor, and social philosopher. He was a professor of psychology at Harvard University from 1958 until his retirement in 1974.

C ...

(1904–1990) published '' Walden Two'' in 1948. The Twin Oaks Community was originally based on his ideas. Ursula K. Le Guin

Ursula Kroeber Le Guin (; October 21, 1929 – January 22, 2018) was an American author best known for her works of speculative fiction, including science fiction works set in her Hainish universe, and the '' Earthsea'' fantasy series. She was ...

(1929-2018) wrote about an impoverished anarchist society in her book ''The Dispossessed

''The Dispossessed'' (in later printings titled ''The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia'') is a 1974 anarchist utopian science fiction novel by American writer Ursula K. Le Guin, one of her seven Hainish Cycle novels. It is one of a small number o ...

'', published in 1974, in which the anarchists agree to leave their home planet and colonize a barely habitable moon in order to avoid a bloody revolution.

Related concepts

Some communities of the modernintentional community

An intentional community is a voluntary residential community which is designed to have a high degree of social cohesion and teamwork from the start. The members of an intentional community typically hold a common social, political, religious ...

movement such as kibbutzim

A kibbutz ( he, קִבּוּץ / , lit. "gathering, clustering"; plural: kibbutzim / ) is an intentional community in Israel that was traditionally based on agriculture. The first kibbutz, established in 1909, was Degania. Today, farming ha ...

could be categorized as utopian socialist. Some religious communities such as the Hutterites

Hutterites (german: link=no, Hutterer), also called Hutterian Brethren (German: ), are a communal ethnoreligious branch of Anabaptists, who, like the Amish and Mennonites, trace their roots to the Radical Reformation of the early 16th cent ...

are categorized as utopian religious socialists.

Classless modes of production in hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fung ...

societies are referred to as primitive communism by Marxists to stress their classless nature.

Notable utopian socialists

*Edward Bellamy

Edward Bellamy (March 26, 1850 – May 22, 1898) was an American author, journalist, and political activist most famous for his utopian novel ''Looking Backward''. Bellamy's vision of a harmonious future world inspired the formation of numerou ...

* Alphonse Toussenel

Alphonse Toussenel (March 17, 1803 – April 30, 1885) was a French naturalist, writer and journalist born in Montreuil-Bellay, a small meadows commune of Angers; he died in Paris on April 30, 1885.

A utopian socialist and a disciple of Charles F ...

* Tommaso Campanella

Tommaso Campanella (; 5 September 1568 – 21 May 1639), baptized Giovanni Domenico Campanella, was an Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, theologian, astrologer, and poet.

He was prosecuted by the Roman Inquisition for heresy in 1594 an ...

* Etienne Cabet

** Icarians

* Victor Considérant

* David Dale

David Dale (6 January 1739–7 March 1806) was a leading Scottish industrialist, merchant and philanthropist during the Scottish Enlightenment period at the end of the 18th century. He was a successful entrepreneur in a number of areas, m ...

* Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier (;; 7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of Fourier's social and moral views, held to be radical ...

** North American Phalanx

The North American Phalanx was a secular utopian socialist commune located in Colts Neck Township, Monmouth County, New Jersey. The community was the longest-lived of about 30 Fourierist Associations in the United States which emerged during a b ...

** '' The Phalanx''

* King Gillette

* Jean-Baptiste Godin

Jean-Baptiste is a male French name, originating with Saint John the Baptist, and sometimes shortened to Baptiste. The name may refer to any of the following:

Persons

* Charles XIV John of Sweden, born Jean-Baptiste Jules Bernadotte, was King o ...

* Laurence Gronlund

* Matti Kurikka

Matti Kurikka (January 24, 1863 Maloye Karlino, Tsarskoselsky Uyezd, Saint Petersburg Governorate, historical Ingria – October 4, 1915 Westerly, Rhode Island, United States) was a Finnish journalist, theosophist, and utopian socialist.

Kuri ...

* John Humphrey Noyes

* Robert Owen

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh people, Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement. He strove to improve factory working conditio ...

* Philippe Buonarroti

:''See also Filippo Buonarroti (1661–1733).''

Filippo Giuseppe Maria Ludovico Buonarroti, more usually referred to under the French version Philippe Buonarroti (11 November 1761 – 16 September 1837), was an Italian utopian socialist, wr ...

* Vaso Pelagić

* Henri de Saint-Simon

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon (17 October 1760 – 19 May 1825), often referred to as Henri de Saint-Simon (), was a French political, economic and socialist theorist and businessman whose thought had a substantial influence on p ...

* William Thompson

* Wilhelm Weitling

Wilhelm Christian Weitling (October 5, 1808 – January 25, 1871) was a German tailor, inventor, radical political activist and one of the first theorists of communism. Weitling gained fame in Europe as a social theorist before he emigrated ...

* Gerrard Winstanley

Gerrard Winstanley (19 October 1609 – 10 September 1676) was an English Protestant religious reformer, political philosopher, and activist during the period of the Commonwealth of England. Winstanley was the leader and one of the found ...

Notable utopian communities

Utopian communities have existed all over the world. In various forms and locations, they have existed continuously in the United States since the 1730s, beginning with Ephrata Cloister, a religious community in what is now Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. ; Owenite communities *New Lanark

New Lanark is a village on the River Clyde, approximately 1.4 miles (2.2 kilometres) from Lanark, in Lanarkshire, and some southeast of Glasgow, Scotland. It was founded in 1785 and opened in 1786 by David Dale, who built cotton mills and hou ...

, Scotland, 1786

* New Harmony, Indiana

New Harmony is a historic town on the Wabash River in Harmony Township, Posey County, Indiana. It lies north of Mount Vernon, the county seat, and is part of the Evansville metropolitan area. The town's population was 789 at the 2010 census. ...

, 1814

; Fourierist communities

* Brook Farm, Massachusetts, 1841

* La Reunion (Dallas), Texas, 1855

* North American Phalanx

The North American Phalanx was a secular utopian socialist commune located in Colts Neck Township, Monmouth County, New Jersey. The community was the longest-lived of about 30 Fourierist Associations in the United States which emerged during a b ...

, New Jersey, 1843

* Silkville, Kansas, 1870

* Utopia, Ohio, 1844

; Icarian communities

* Corning, Iowa, 1860

; Anarchist communities

* Home, Washington, 1898

* Life and Labor Commune, Moscow Oblast, Soviet Union (Russia), 1921

* Socialist Community of Modern Times, New York, 1851

* Whiteway Colony, United Kingdom, 1898

; Others

* Fairhope Alabama, USA, 1894

* Kaweah Colony, California, 1886

* Llano del Rio, California, 1914

* Los Mochis, Sinaloa, Mexico, 1893

* Nevada City, Nevada, 1916

* New Australia, Paraguay, 1893

* Oneida Community, New York, 1848

* Ruskin Colony, Tennessee, 1894

* Rugby, Tennessee, 1880

* Sointula, British Columbia, Canada, 1901

See also

* Pre-Marx socialists * Pre-Marxist communism * Christian socialism * Communist utopia * Diggers * Ethical socialism * Futurism * History of socialism * Ideal (ethics) * Intentional communities * Kibbutz * List of anarchist communities *Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

* Nanosocialism

* Post-capitalism

* Post-scarcity

* Radicalism (historical)

* Ricardian socialism

* Scientific socialism

* Socialism

* Socialist economics

* Syndicalism

* ''Utopia for Realists (book), Utopia for Realists''

* Yellow socialism

* Zero waste

References

Further reading

* Keith Taylor (political scientist), Taylor, Keith (1992). ''The political ideas of Utopian socialists''. London: Cass. .External links

*Be Utopian: Demand the Realistic

by Robert Pollin, ''The Nation'', March 9, 2009. {{DEFAULTSORT:Utopian Socialism Utopian socialism, History of social movements Idealism Radicalism (historical) Social theories Socialism Syndicalism Types of socialism